Cynicism is a strange status symbol for a world that keeps getting better

Everything incentivizes pessimism.

I meet an astounding number of pessimists as a financial journalist.

Despite covering the world’s progress in real time, people in media and finance can’t seem to shake their perennial bearishness. Spend a day in a newsroom or hedge fund, and the mood centers on what’s about to break.

It’s a strange paradox. The professions best equipped to assess the future are the least hopeful about it.

I’ve come to see that disconnect as one of the great blind spots of legacy institutions.

My own optimism felt out of place when I worked at Business Insider. There, like elsewhere across mainstream media, you find an improbable number of business reporters who detest business and tech reporters who can’t stand new technology.

Just the same, I speak daily with Wall Street professionals who are more eager to share what they’re betting against than investments they think will appreciate over time.

Much of this is a problem of incentives. In both media and markets, pessimism sounds intelligent. It signals status and conveys a sense of being “in the know.”

For journalists, bad news gets more clicks and airtime. A splashy takedown piece is more likely to lead to a promotion than a story about incremental problem-solvers.

One study that analyzed half a billion social media posts and 95,000 news items found that users were nearly twice as likely to share links to negative-sounding news articles.

The old newspaper cliché sticks for a reason: “If it bleeds, it leads.”

In finance, incentives can skew bearish too. Investors who warn of catastrophe sound prudent and risk-conscious, whether or not they end up being correct.

One veteran trader I know has been warning me for two years that the stock market will crash.

He was briefly validated in April when stocks declined following President Trump’s “Liberation Day” announcement on tariffs, though the market has since rebounded to all-time highs.

He’s correct to argue that no one wants to be the last bull standing before a downturn. But the long view negates his point.

There’s plenty of research around how pessimism is good for business. Psychologists call it negativity dominance. Our brains have long been wired to respond more to threats than good news.

It’s easy to see why, in a professional setting, this bias gets mistaken for high IQ.

Not only that, but skepticism doesn’t sound like salesmanship the way optimism often does. If anything, adopting a downbeat outlook can come across as legitimizing.

Swedish researcher Hans Rosling wrote in Factfulness that people instinctively look for guilty parties when something goes wrong. That impulse shapes the way journalists frame the news.

Often, this bias assigns heroes and villains to stories that could be better explained by systems and accidents.

The result is a corporate media culture that over-indexes to fault and blame, whether it’s warranted or not.

And so you have entire industries that signal credibility with cynicism.

That institutional stance in turn attracts those types of people, and the pessimism becomes entrenched as both worldview and operating principle.

I have more anecdotal evidence in media than finance, and I’ve seen firsthand how optimism is snuffed out like a newsroom contagion.

A reporter who wants to highlight what’s working is labeled as a corporate shill. Being too bullish — even when the data justify it — is considered reckless or partisan.

Data-backed optimism

When you zoom out, the case for pessimism simply is not backed by the numbers.

Over any meaningful timeframe, the world has improved across every key metric.

Global poverty has collapsed from 38% in 1990 to about 8% today

Life expectancy has doubled in the last century

Child mortality has dropped 51% since 2000

Global literacy has gone from 20% to 90% in the last century

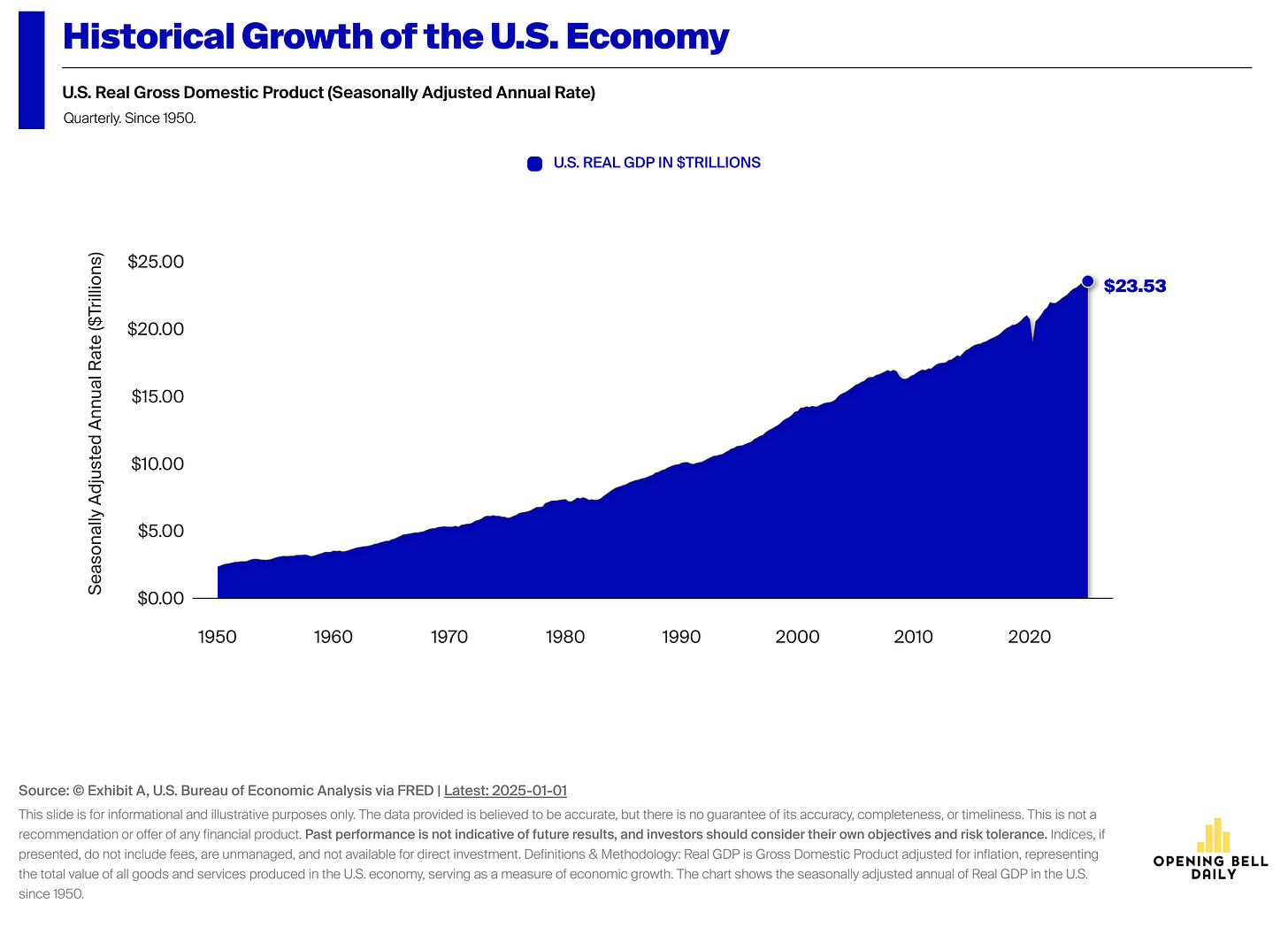

This upward trajectory is captured in the chart below, mapping what’s effectively been $23 trillion in uninterrupted US economic growth since 1950.

Stable progress across history is in fact normal. You just wouldn’t know it by looking at the news.

Compare the above chart to the one below of the University of Michigan consumer sentiment report. It’s one of the most-cited surveys in the financial press, even though it has very little predictive power about the actual economy.

While the economy remains robust, the sentiment survey is trending near levels seen during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis.

The dissonance is glaring but predictable. The world keeps getting richer, fewer people are impoverished, and more people are educated.

Yet the “vibes” suggest collapse is imminent.

You’d think the people paid to monitor all this — reporters, analysts, academics, fund managers — would be the first to call out these trends, but most don’t.

Compounding, systemic progress is invisible to our instincts and doesn’t trigger our threat systems. None of this makes for a juicy headline or compelling short-trade idea, and it doesn’t demand attention the way doomerism does.

My colleagues in media and finance always have to wrestle with this paradox.

The more informed someone is, the more prone they are to allow short-term turbulence to distort their perception of the undeniable, unrelenting long-term trend.

To be sure, not all journalists are cynical Luddites just as not all financiers are short-selling Cassandras.

Video journalist Cleo Abram has built a successful show, Huge if True, on the premise that technology constantly makes the future better, and I can point to a number of Wall Street strategists who are consistently optimistic to the point of being labeled contrarian.

What’s more, it’s worth highlighting that the structural limitations of legacy institutions — advertising pressures, editorial mandates, regulatory frameworks — aren’t conducive to risk-taking and nuance. These, too, impact tone and coverage.

Founder mode

Since moving to New York in 2021, I feel lucky to have met so many people launching startups and building products.

This cohort has ignited a level of optimism in me that I never found among even the smartest, most competent colleagues of mine in the press.

I now straddle both groups as a founder in media. It’s helped me keep the upbeat, forward tilt of a builder without losing the critical lens of a reporter.

Startup people have no choice but to live in the future. It’s a different world than the news business, because “news” by definition is in the past.

Because founders bet on progress and abundance, in a way that makes them more honest prognosticators of where the world is heading.

That said, in the same way the media has incentives to publish doom-and-gloom, founders are often rewarded for stretching their optimism to the point of fiction if it means new investment or more customers.

Elizabeth Holmes took optimism to an extreme degree. Her blood-testing startup Theranos raised over $700 million on promises of a technology that never worked.

Sam Bankman-Fried did the same in crypto with FTX, packaging fraud as innovation well enough to win over investors and politicians.

Both founders are currently in prison.

Still, the same bottlenecks that a startup founder sees as opportunity could be categorized by a journalist as a risk that’s not worth exploring.

There’s value in both instincts. But only one builds the future.

Phil Rosen

Co-founder & Editor-in-Chief, Opening Bell Daily

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this post, consider hitting the “like” button to help boost visibility. If the ideas resonated, I’d love to hear why — reply directly to this email or leave a comment below.

nice article

Great article. I would add that so many journalists nowadays are young/woke and have an overly-cynical view of America and capitalism in general. That carries over into the financial news reporting sector as well. You add in the fact that these journalists mostly despise Trump and these pessimistic/bearish sentiments are compounded. As one small example... I'm as concerned about the national debt as the next person, but few journalists had anything to say about it when trillions of dollars in Covid relief and Biden-era policies (like the Infrastructure Bill) were being approved left and right. But now that Trump wants to extend the 2017 tax cuts, the national debt suddenly matters and is a grave threat to our fiscal future.